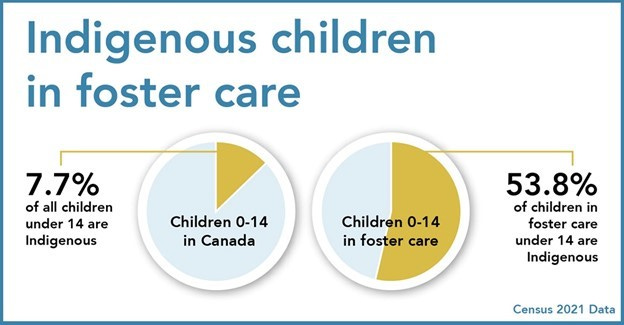

In Canada, Indigenous under 15 years old make up more than 50% the total foster care population, yet they represent less than 8% of all Canadian children:

When those children age-out, many soon become street people or part of the country’s jail population. According to Statistics Canada: In 2020/2021, Indigenous people in Canada were incarcerated at a much higher rate than non-Indigenous people. On an average day that year there were 42.6 Indigenous people in provincial custody per 10,000 population compared to 4.0 non-Indigenous people.

The politically correct term for this is overrepresentation, suggesting that the fault lies with social services, policing, the courts, etc., rather than due in any part to broken Indigenous culture. Can more money fix this?

The Assembly of First Nations Chiefs say so, and they also say that a $47.8 Billion offer from the federal government for compensation and Indigenous-controlled family services, is not enough. Roughly half of that money would go to individuals who were removed from their dysfunctional families and the other half would go into First Nations’ on-reserve budgets to help implement their own, culturally appropriate, child welfare systems.

But the thing is since the 2016 Human Rights findings and subsequent Indigenous class action which prompted the $47.8 Billion solution, federal monies for on-reserve child welfare have been upped and now off-reserve (including non-indigenous) funding levels are lower. This is confirmed in the March 2022 report from the BC Representative for Children and Youth, titled At a Crossroads:

First Nations, Métis, Inuit and Urban Indigenous children living off-reserve are at the greatest disadvantage because provincial funding for services for them is much less than for their counterparts living on-reserve.

The difference in funding levels is largely due to the Canadian Human Rights Tribunal ruling of 2016 that determined that funding practices for First Nations children living on-reserve were discriminatory, and that effectively forced the federal government to pay for on-reserve child welfare services at actual costs, based on a needs-based budget that includes culturally rooted prevention services. However, provincial funding has not kept up

So, on-reserve child welfare transfers have been increased to cover actual costs as budgeted and reported by the various First Nations, yet another $23+ Billion is needed … huh? The other $23+ Billion will be paid to Indigenous who were taken out of a dangerous family environment for their own safety and now may be living fulfilled lives because of the 2nd chance offered by their foster care … huh?

One of the poster-child plaintiffs in this boondoggle is Ashley Bach, who was removed at birth from her Vancouver Downtown Eastside heroin-addicted mother and then placed into foster care, leading to adoption with a family in Langley BC. Her ancestral First Nation is on the Mishkeegogamang reserve about 500 km north-west of Thunder Bay, Ontario:

Olivia Stefanovich/CBC

Ashley presents herself as a victim of colonial racism. She was interviewed by The Tyee:

Tyee - What could the government have done differently to prevent you from going into care in the first place?

Ashley - A lot of things they could have done. My grandmother went to residential school up in Sioux Lookout, and that really messed her up. My mom was born on the rez north of Sioux Lookout and they ended up in Thunder Bay and then my mom went into foster care. She ran away when she was 16 or 17 and got addicted to heroin, ended up on [Vancouver’s] Downtown Eastside and so that’s why I went into care. If the government hadn’t done all of these terrible things, that would have been the best way to have prevented me from ending up in care.

Tyee - What could child welfare services have done to improve your experience in care?

Ashley - I think a lot of it would have come down to education and programs. First off, it would have been great if my parents had more of an understanding of Indigenous people, if they had also understood the issues of racism. I was absorbing all these things around me, and they were things that they wouldn’t notice because they’re not native.

The other issue is my community is on the other side of the country from where I grew up, and that’s hard. I’ve been there once, and the only way I managed to get there was I got funded to do research on climate change with my community, that’s the only time I’ve been there. It would have been great if the child welfare services had some sort of program or funding to help their youth in care maintain connections and build connections with people in their communities. Because that’s something I’m never going to have.

I’m in environmental science, and I literally didn’t grow up in a place where I should have. I grew up out west, so I can picture plants and animals — I’m very visual. But up north where my community is, I didn’t grow up with that, I didn’t get any of that.

So, first Ashley plays the residential school trauma card, then trumps it declaring ignorant white parenting, and completes the trick citing inadequate government support. Somehow she still ended up with a BSc from McGill, a MSc from Johns Hopkins and is finishing her Law degree at Lakehead University.

Her welfare justice resume is already impressive. She recently gave a speech as part of her fight for truth and reconciliation – October 16, 2024 Address to the Chiefs of Ontario. It includes:

For me the colonial child welfare system did exactly what it was designed to do. It removed me from my community, from my culture, from my language and from my homelands; and it discouraged me from finding my home fire and finding my identity as a Nishnawbe.

I learned that I was identified as a child that had special needs, that would never be able to be met in Mish’ despite having family there because Mish’ is a really remote community and services would be too far away and too expensive to provide. I learned that the Chief and Council of Mish’ at the time wrote to the BC Ministry of Children and Family Development saying that: “There is no possible means of providing the special needs required by this child. There is simply no resources or facilities in our community that would enable the child of the best care possible.”

Ashley purports that removal from her drug addicted mother was all part of a nefarious colonial plan. Why then did that evil system bother to contact the Mish’ Council, prompting a reply that their First Nation couldn’t accept the return of Ashley to her Nishnawbe home?

It seems that Ashley’s fantasy child welfare overhaul would require the funding of complex mental health treatment in every First Nation hamlet coast-to-coast, with trained medical staff (Indigenous of course) standing by to receive addiction-displaced children wherever they may pop up. Better move the decimal place over on that federal settlement.

And how would Ashley have fared if the Mish’ Council had taken her back? She likely would have received a strong environmental science understanding at a wilderness level. However, according to the 2016 Mishkeegogamang Census only 13% of their youth finished high school and 0% went on to higher education, so she probably wouldn’t have become the eco-scholar she is now. Also, if she was part of the 30% that achieved on-reserve employment, her salary probably wouldn’t get to the level she will enjoy as an activist lawyer, given that the 2016 median Mish’ income was just $10,784.

The reparation payments from the ridiculous $47.8 Billion rejected by the Chiefs, will absurdly go to Ashley, who appears to be fabricating a hardship story out of guilt about her privileged upbringing, and those like her who have benefited from the colonial child welfare system. Others on the wrong end of the experience, and perhaps living on the streets, will likely use the windfall to shorten their lives.

The on-reserve Indigenous child welfare system is already fully funded - if a First Nation needs more, they submit their budget and the additional funds are transferred. According to their 2023 Annual Report the Mishkeegogamang have revenues of about $40 Million per year, and have accumulated roughly $20 Million cash in the bank. If there are child welfare needs not being met there, it is not due to lack of money.

What will on-reserve programs achieve with the huge federal settlement excess … maybe everyone gets their own personal social worker? (LOL) They would likely say “It’s a good start”, and then the drums begin thumping again.